![]()

under the patronage of St Joseph and St Dominic

By the rivers of Babylon there

we sat and wept, remembering Zion;

on the poplars that grew there we hung up our harps. . . Ps 136

|

under the patronage of St Joseph and St Dominic By the rivers of Babylon there

we sat and wept, remembering Zion; |

|

|

EXPLAINING THE VOYAGER DISASTER

Download this document as a

"A naval officer isn't supposed to speculate about his orders. He's supposed to execute them." Herman Wouk, The Caine Mutiny, Ch. 13 On the night of Monday, 10th February, 1964, at about 8.56 pm Australian Eastern Standard Time (2056 hrs), in the Tasman Sea some 19 nautical miles south-east of Point Perpendicular, Jervis Bay's northern head, the Daring Class Destroyer, Voyager, under the command of Captain Duncan Stevens collided with the Aircraft Carrier, Melbourne, commanded by Captain John Robertson. The Melbourne cut the Voyager in two and eighty two men died, including her captain. The Prime Minister, Mr Robert Menzies, ordered an enquiry. He had wanted one headed by a judge aided by naval assessors but discovered the legislative framework to enable this did not exist. He established, instead, a Royal Commission headed by the head of the Industrial Court, Sir John Spicer. This enquiry, sat from 25th February to 25th June 1964 and Sir John Spicer's findings were published on 26th August following. They enjoyed a less than enthusiastic reception from critics and from the Australian public. In due course, in 1967, there occurred a second Royal Commission. The primary evidence of the reason for the navigational failure was always going to come from the survivors of the Voyager. There were, providentially, sufficient of them from the vessel's various stations for the cause of that failure to be determined. There was, moreover, evidence from an earlier ‘survivor’ of the Voyager, her previous executive officer, retired Lieutenant Commander Peter Cabban, to fill out any lacunae in the evidence. Regrettably, the conduct of counsel assisting the first Commission, coupled with the Commissioner’s own lack of insight into the issues, prevented the cause from being revealed. With the special interest each had in protecting his client from blame, the barristers representing the various parties involved in the disaster had little investment in ensuring that the enquiry arrived at the truth. Sir Garfield Barwick spoke to the point when he said “the only resemblance between a Royal Commission and a Court of Justice is the furniture in the courtroom”.[1] ************* Melbourne had recently undergone a refit. Late in the afternoon of 10th February 1964, the two vessels prepared for night flying exercises with aircraft from the Naval Air Station at nearby Nowra due to practise touch-and-go landings on the carrier's deck in anticipation of their permanent return to the vessel. Naval historian Tom Frame wrote: "At 1830, the ships were 20 miles to the south-east of Jervis Bay in deep water. There was a low easterly swell, smooth seas and light variable winds... There was no moon, the night was clear, and visibility was estimated at 20 miles."[2] Sunset was at about 1845. The time standard was the same summer and winter: Daylight Saving Time was not to be introduced in New South Wales for another seven years. "Melbourne and Voyager were 'darkened' for the exercise, with only operational lighting visible to the other ship. This consisted of the green starboard and red port sidelights, a white stern or overtaking light, masthead lights and, in the case of Melbourne, the experimental flight-deck floodlighting which was meant to have been visible only on the port side to avoid being mistaken for the port sidelight. The two sidelights in the carrier were dimmed so that their visibility range was about one nautical mile... without binoculars..."[3] From 1930 hrs the two vessels were engaged in flying operations with Voyager performing plane guard duties which placed the destroyer 1,000 to 1,500 yards off the carrier's port quarter at a relative bearing of 20° (160° relative, or red 160, for Melbourne). The Melbourne's captain tried different courses in an endeavour to maximise the air flow over the carrier's deck to assist the operations of the pilots, variously 000, 175 and 190, which manoeuvres placed the accompanying destroyer sometimes behind, sometimes ahead, of the carrier. At about 2046 he sent a signal to the Voyager, “Turn 060”, which is interpreted, “Turn together to 060, ships turning to starboard”.[4] At the time Voyager was 1000 yards astern of Melbourne: this order had the effect of placing her some 1,000 yards ahead of the carrier and off her starboard bow. At about 2051 Robertson sent a further signal to Voyager: “020 Turn”. The interpretation is “Turn together to 020, ships turning to port”. One of the surviving tactical operators from Voyager's bridge, the operator having responsibility for communications, Gary Evans, attested that Voyager settled on course 020 after this turning signal.

The manoeuvre Melbourne expected Voyager to conduct  Half a minute later, and some 3 mins 50 secs prior to the collision,[5] Melbourne, sent a flying course signal to Voyager in the following terms: “Foxtrot Corpen 020 Tack 22”. This is interpreted – “Estimated course for impending aircraft operation is 020 at a speed of 22 knots”. Evans said he acknowledged this signal and passed it to Voyager’s Officer of the Watch, (RN) Lieutenant David Price, who gave the order 'starboard 15'. But about 45 seconds later this order was overridden with an order, or orders, of which the ultimate was “port 10”.[6] Since they led to the collision, who gave those orders and why they were given were the proximate issues for determination by the enquiry. Voyager continued to turn to port until a point in time about thirty seconds prior to impact when Stevens gave the emergency order “full ahead both engines; hard a- starboard”.[7] This order involving, as it did a violent turn at speed, had the effect of initiating the laying-over of the vessel to port ensuring that when Melbourne collided with her, Voyager's superstructure was the first thing hit. The order almost certainly prevented Voyager from penetrating Melbourne's starboard side a short distance aft of the bow with an impact which, at a speed of some 20 knots, must have eviscerated the carrier, almost certainly resulting in the loss of both vessels, and a much greater number of casualties than in fact occurred.

Comment The determination of the issues turned on the evidence of Evans as the Tactical Operator handling communications with the Melbourne. Here is Tom Frame's analysis: “While keeping his watch on the bridge of Voyager, Tactical Operator Gary Evans sat in front of the captain's chair and could remember Stevens being seated with the Communications Yeoman, Kevin Cullen, at Stevens' right hand. On the night of the collision he had been using a telephone style handset to receive and acknowledge VHF voice signals from Melbourne. Evans stated that when the turning signal was received he reported it to Price, apparently within the hearing of Stevens and Cullen. However, he did not report any of the signals received that night directly to Stevens and could not be certain that Stevens had actually heard any of them. It is possible, with the background noise associated with steaming at more than 20 knots, that neither Price nor Cullen actually heard the signal over the tactical primary loudspeaker which projected distorted sound. The signal was acknowledged by Price. Evans stated that Voyager steadied on 020 degrees before receiving and acting on the flying course signal.”[8] Frame confesses his bemusement over Evans' evidence: “Evans was in a key position as the tactical operator on duty on the bridge. He may have been the only member of the bridge staff to have actually heard Melbourne's turning course and flying course signals. Evans said he believed the cause of the collision was that Melbourne gave a final order to turn to port and failed to turn herself, or was slow to turn. It was a curious explanation for someone who had been on Voyager's bridge and who had personally received all Melbourne's signals. In fairness to Evans, it should be stated that in giving his evidence he did not want to be held to the accuracy of any of the courses he recalled prior to the collision...”[9]

The contradictions are patent. A closer analysis reveals that the evidence Evans gave the enquiry differed in critical respects from views he had originally expressed. The enquiry discovered this alteration in his views almost by accident. Leading Seaman Michael Patterson, a survivor from Voyager's operations room, gave evidence on the 21st day of the hearing. Some time later he read a newspaper account of the evidence which Evans had given earlier (on the 14th day) and realised that Evans had omitted something vital, mention of a cry he, Patterson, had heard in the water after the collision, uttered by one of the survivors from the bridge, “Melbourne told us to turn to 270 and she didn't!” Patterson was later to identify the voice as that of Evans. This departs radically from Evans’ expression, amounting to no more than opinion, in evidence that the cause of the collision was that Melbourne gave a final order to turn to port and failed to turn herself, or was slow to turn. In confirmation of his recollection of the cry, and of his attribution of it to Evans, Patterson said that he had spoken to Owen Sparks, another Tactical Operator from the Voyager. “Sparks said that he saw Evans in Balmoral [Naval] Hospital and Evans had told him that Melbourne had told Voyager to turn. Evans also told Tactical Operator Burdett something similar outside this court.”[10] Frame adds this revealing note of Patterson's evidence on Day 28 of the evidence: “Patterson spoke with Evans about these matters on two occasions. He states that on neither occasion did Evans make any comment.”[11] Patterson was not the only survivor who had heard the cry. Another survivor, Able Seaman Andrew Matthews, said that while in the water he heard a voice call out "Melbourne didn't turn; Melbourne didn't turn."[12] In the statement he made in anticipation of the Commission hearings (dated 4th March 1964), Evans said that the first two elements of Melbourne's final signal, corpen and foxtrot, had been reversed. A signal corpen foxtrot... signified “estimated course for flying operations”. Its reverse, foxtrot corpen... signified “turn to the flying course”. The significance of the difference in the signals lay in this: a flying course signal permitted Voyager to use her own discretion: a turning signal gave Voyager no discretion; she must comply and maintain her relative bearing to Melbourne as she turned. Hence, in his statement Evans was saying that Melbourne's final signal required Voyager to comply. Yet it is clear that Melbourne's final signal was a flying course signal allowing Voyager discretion in compliance. When he came to give evidence, however, Evans resiled from this view: he now said that he accepted that the final signal had been in the form corpen foxtrot... He was cross examined on the change by Leycester Meares QC (for the late Lieutenant Price) and agreed that the reason he had altered his view, was that Melbourne had already given a turning signal (to 020) and it made no sense that the last signal, which also read 020, should also be a turning signal. Why had Evans, the one survivor closest to the executive functions on Voyager's bridge, been so insistent that the final signal from Melbourne was a turning signal, so vehement that Melbourne had required Voyager to turn to the west, and then modified, or moderated, his view? And, perhaps even more importantly, how could Evans have arrived at those views in the first place when he had heard, and acknowledged, Melbourne's last signal, and transmitted it for what it was, a flying course signal at 020, to the Officer of the Watch, Lieutenant Price? No critic of the evidence at the enquiry appears to have drawn the obvious conclusion about the implications of Voyager's final movements and how they are consistent with Evans’ cry in the water after the collision.

******************

The Officer of the Watch on Voyager was (RN) Lieutenant David Price. Retired Lieutenant Commander Peter Cabban later attested to Price's worth: “[T]he officer of the watch of Voyager at the time of the collision had just completed a long period, I think probably twelve months, at HMAS Watson as instructor in the tactical floor so that his ship handling knowledge, although he may not have served in destroyers, should have been as good as any officer on board.”[13] As Officer of the Watch, Price— “was the captain's representative on the bridge, and every officer on board, regardless of rank, was subject to him.”[14] It was his duty— “to take care that he is never prevented, through over-attention to detail, from discharging his primary responsibility for the safety of the ship.”[15] There was only one man on the ship who could override Price's orders and his authority—Captain Stevens. A vessel's port and starboard navigation lights shine from dead ahead to a line angling away from amidships two points abaft the beam.[16] Melbourne's starboard light shone through an arc of 112½° (90° + 22½°).from dead ahead. Had Voyager turned together with Melbourne forthwith on the supposed last turning signal, Melbourne's starboard navigation light would, in all likelihood, have remained in view for Voyager. At the time of this signal, relative to Melbourne, Voyager bore about green 20 (i.e., ahead and slightly to starboard of her). Had the two vessels turned to port together that relative bearing ought to have translated into a new bearing of about green 100 from Melbourne. But Voyager had turned away to starboard, and then steadied on a nor ‘easterly course (032 or perhaps 065) at a speed of about 20 knots over a period of close to one minute. On these supposed facts, once Voyager turned back to port her bearing from Melbourne ought to have been of the order of green 150, and since Melbourne's starboard light occludes at green 122.5 (112½°), it should have disappeared from view. One and half minutes or so prior to the collision, O/S Brian Sumpter, Voyager's port side watch, said he became apprehensive about what he regarded as Melbourne's looming presence. He called “Bridge!” and turned to see Lieutenant Price observing Melbourne through binoculars. At this point Melbourne was some 1,200 yards distant on a bearing relative to Voyager of about red 60 and the two vessels were closing rapidly. Why was Price doing this? Acting in accordance with the view - whatever its source - that ruled on Voyager’s bridge, that Melbourne's last signal was a turning signal and the course Melbourne had mandated was not 020 but some westerly, or sou’westerly course, Price was endeavouring to solve a puzzle. Melbourne's distance from Voyager was difficult to assess in the darkness: her faint profile was not square-on, as the outline of the carrier would appear in plan elevation, but angled. It was consistent with the profile Melbourne should have presented turning away from Voyager save for one feature. Melbourne's starboard navigation light was still visible! It was this conundrum Price was endeavouring to resolve. The only officer who could override Price's order, grounded on the information Evans had originally supplied him, was Captain Stevens. It follows that the originator, or endorser, of the twofold error involving Melbourne's final signal, was Stevens. What follows? Evans original statement that the last signal from Melbourne was a turning signal reflected the interpretation that Stevens had imposed upon Voyager's bridge staff. Evans’ vehement assertion that Melbourne had ordered a “turn to 270” was the interpretation of Stevens. Time and reflection had brought Evans to the realisation that neither perception could have been right. There was no turning signal: there was no signal requiring Voyager to turn to the west. These false perceptions had grounded the orders that had led inevitably to the collision. Not only was the loss of Voyager and the 81 men who had died with him technically imputable to Stevens as the vessel's Captain, but the losses were morally imputable to him as well. Loyalty to his late captain prevented Evans from excoriating him for the blunder. How did Stevens come so to misunderstand Melbourne's final signal? Stevens was a man dependent on alcohol. The evidence of his behaviour during the time Cabban served under him on Voyager prior to his resigning from the Service demonstrates that Stevens was an alcoholic whose grasp of the demands of his office of captain had become dulled to the point where any action he took might put his ship and its crew in danger. Less than 90 minutes prior to Voyager's final critical moments Stevens had imbibed a substantial quantity of alcohol, a triple brandy, provided him by Ordinary Steward Barry Hyland.[17] It is open to conclude that his misunderstanding of the signal resulted from the garbled sound of the tactical primary loud speaker (which reproduced the radio telephone communications monitored by T/O Evans) coupled with effects of the alcohol he had imbibed. Cabban's recollections are significant— "[Stevens] was inclined to become (sic) under the influence very quickly and he drank very large glasses of alcohol. His standard brandy on these occasions would be almost half a tumbler full of brandy topped up with water."[18] This quantity agrees with the measure Hyland said he provided to Stevens at 1930 hrs. One cannot know exactly what transpired on Voyager's bridge, but an exploration of the probabilities assists. The relevant officers apart from the captain were the executive officer, Lieutenant Commander Ian MacGregor; the Navigating Officer, Lieutenant Harry Cook; and Price, the Officer of the Watch. There is no indication that any were aware of Stevens’ recent ingestion of alcohol. Each would defer to Stevens’ view of Melbourne's final signal because he was the Captain and because the manner in which he was accustomed to exercise his authority militated against his officers offering a contrary view.

Cabban’s earlier experience of Stevens assists: “He was subject to violent outbursts at the officer of the watch if he was either slow to react or if he made a mistake... This extended even to abuse of the officers of the watch over the armament broadcast from the operations room... His temperament could range from buoyant good humour to depression...”[19]

Support for the view that this assessment continued to apply after Cabban had left the ship and the Navy, is to be found in the report by Tom Frame that Lieutenant Cook, Voyager's navigating officer, had confided in one of his Naval College team mates, Lieutenant Paul Berger, over lunch on the Melbourne the day prior to the collision, that Stevens had been “riding” him very heavily and that he was not looking forward to the coming week.[20] Stevens’ behaviour had the effect of cowing subordinates not possessed of a strength of character sufficient to resist him as Cabban had done when he served under him. In the course of his evidence in the second enquiry, Cabban was to draw a parallel between his experience of Stevens’ behaviour and that of the fictional Captain Phillip Queeg in Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny. Cabban was mocked for doing so by the legal representatives of those who had an interest in destroying the force of his evidence. How many of them, one must wonder, had troubled to read the American novel to weigh the description of the personal and moral shortcomings of its tyrannical subject, or the telling description of the effect of such tyranny upon those trained to obey every order of their captain? The probabilities are that a conviction of the rectitude of his own opinions over those volunteered by his officers, incident to the arrogance and blindness to his own defects which marked Stevens’ character aggravated by his ingestion of alcohol, prevented him from entertaining a doubt that he had been in error in so interpreting the signal. If any officer had suggested that he have the signal confirmed by the Melbourne the probabilities are that the same character defect would have militated against him following the suggestion. In Ian McGregor, Voyager lacked an executive officer of Cabban’s force of character. MacGregor had served with Stevens before and, according to Frame, the two liked each other's company.[21] Cabban said that when he handed over to MacGregor he had spent about half an hour discussing with him the problem posed by the Captain's drinking, and stressed to him most strongly— “the necessity for the officers in the wardroom not to drink at sea because of the Captain's habit. [MacGregor] replied that he was capable of making his own decision in this matter and didn't agree with me…”[22]

MacGregor played little part in the crucial few minutes following the final signal from Melbourne. Frame reports Patterson, a survivor from Voyager's operations room, as saying that, as the ship was making her final critical turn to port, MacGregor had asked him whether he had either Melbourne or Tabard (the Royal Navy's submarine) on radar. The question demonstrates a fundamental lack of grasp of the tactical situation. Tabard was some 20 miles away. Given his predisposition in favour of Stevens, it is unlikely that MacGregor would have opposed him. That Price was either convinced of, or overborn by, the force of Stevens' opinion on the final signal may be gathered from Sumpter's evidence of his behaviour in the minutes prior to the collision. Sumpter said that he seemed mesmerised. It seems clear that Price was no longer in charge of the ship: he had been overruled by the Captain. Cook, the Navigation Officer, was already intimidated by Stevens and bound to defer to his opinion, as he was bound to obey his orders. The critical issue, whose refusal of address prevented the first enquiry arriving at the correct conclusion over the cause of the disaster, is this: how could Evans, who had heard the signal from Melbourne (Foxtrot Corpen 020 Tack 22), have come to reject the evidence of his own senses and to hold, a) that the signal had been a turning signal, and not a flying course signal; and, b), that the course indicated was not 020 but some westerly, or sou'westerly play on these figures—whether 220 or 200? The answer lies, I suggest, in Stevens' autocratic style coupled with the disposition instilled in every junior officer to defer to his captain's greater experience and knowledge and to obey him unquestioningly - Evans was only 19. Not only was he taught to submit his will to that of the Captain, but also to submit his intellect to the Captain's intellect, a situation aptly summarised in the quotation from Wouk in the epigraph to this article. The reality of this submission provides the only satisfactory explanation for the contradiction in Evans’ behaviour at the time, and subsequently.

The initial turn to starboard Price had ordered was consistent with a flying course signal and confirms it as such. The subsequent turn to port was consistent with a turning signal, that is, consistent with the misunderstanding that Melbourne had ordered Voyager to turn with her and consistent with Evans, the ship’s tactical operator, adopting that misunderstanding as true despite having himself heard the very contrary signal. When he cried out in the water “Melbourne told us to turn to 270 but she didn’t!” he was defending the perception, and the subsequent order, of his Captain.

The professional advocate will be aware of the rule of fairness that demands that before a submission along the lines contended here could have been made to the one Commission or to the other, its terms had first to be put to Evans. As far as the writer is aware no such submission was ever made and, accordingly, one must assume its terms were never put to Evans. Evans died on February 14th, 2023 at White Beach on the Tasman Peninsula.

Peter Cabban died on August 17th, 2019 in Whitefish, Montana, USA.

Bibliography: Tom Frame, Where Fate Calls, the HMAS Voyager Tragedy, Sydney (Hodder & Stoughton), 1992 Tom Frame, The Cruel Legacy, The HMAS Voyager Tragedy, Sydney (Allen & Unwin), 2005 Peter Cabban and David Salter, Breaking Ranks, The True Story behind the HMAS Voyager Scandal, Sydney (Random House), 2005 ______________________________________________

Appendix

Cabban, his Character and Misfortunes The second enquiry (Royal Commission) was precipitated by the leaking of a statement, the transcript of a tape recording made by Cabban for Captain Robertson at Robertson’s request, detailing what he remembered of Stevens’ conduct in 1963 on an undertaking that it would be made available unattributively to retired New Zealand Vice Admiral Harold Hickling with whom Robertson was writing a book on the incident. The statement became public property after a politician, John Jess, obtained access to it: it was the catalyst that precipitated the second Royal Commission.

Cabban’s character was perceived as a difficult one because he was a stickler for rectitude. Many of those he commanded hated him; but many respected him. In the end the consensus was that he was hard but fair. Among his peers and superiors there were those who respected him and an equal number who did not.

Much was made by counsel at the second enquiry of an earlier determination by the Navy to discontinue Cabban’s qualification as pilot with the fleet air arm on the ground that this had coloured his account of Stevens’ character. Not only was Cabban a competent pilot but a capable one, experienced in flying, navigating and coping with difficult conditions in a variety of aircraft. So well had his superiors regarded him that they him appointed maintenance test pilot at the Navy Base at Nowra. His competence was demonstrated by his successful recovery and safe landing of a severely compromised Fairey Gannet reconnaissance aircraft in a test flight against the expectations of his passenger, the senior instructor, that he and Cabban would die.

The Gannet, a complicated aircraft with high wing loading, was reliant on the efficient working of its twin contra-rotating propellers linked to an immensely powerful double turbo-prop engine. It was established subsequent to the incident that the propellers on the tested plane had been installed incorrectly with the result that the ‘port’ propeller misbehaved. The consequence was that the torque balance was lost. On approach to an emergency landing at the base airfield the aircraft rotated about its (longitudinal) axis beyond 90 degrees. Cabban succeeded in correcting the roll and, as the safest option, elected to crash land the plane beside the strip. Both men survived.

Cabban’s character traits loomed in the establishment of the board established to consider the loss of the plane. Of the three men chosen only one was a pilot, that is, only one man was familiar with the exigencies that confront the pilot of an aircraft in an emergency. The majority were determined to find him at fault and did so and his flying qualification was withdrawn.

Cabban suffered the fate which has become notorious of ‘whistle blowers’ in the modern era. He was betrayed by many of his superiors and his peers, of whose integrity he had felt assured, including a fellow officer who was to acknowledge his failure to support Cabban before he died.

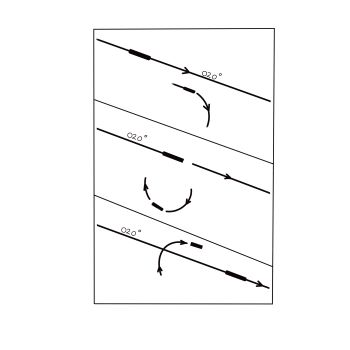

Ship Handling There is nothing to indicate that Cabban’s ship handling was other than exemplary. After the accident he was consulted by the Commonwealth Police as to the appropriate course that Voyager should have taken in response to the signal to take up station to the rear of Melbourne. His advice contrasts with that set out in the diagram above. “I explained that the officer of the watch was expected to act instantly on execution of the carrier’s signals, ordering a change of station for the destroyer. Put simply, the plane guard destroyer was to change position relative to the carrier, from being clear of aircraft taking off, close on the starboard bow, to a position that was clear of landing aircraft, well to the left of the approach on the port quarter… [It] was normal for the initial turn to be made sharply to starboard, reducing speed and relative bearing from the carrier as it continued on course, then turning with the wheel reversed to port while increasing speed when the carrier’s relative bearing was 180 degrees, to pass astern of the carrier, slipping into the new position then adopting the carrier’s course. This manoeuvre – which sounds more complicated than the reality – is known as a ‘fish tail’ because the wake of the destroyer, seen from the air, resembled the movement of a fish tail…” (Breaking Ranks, p. 186)

In contrast, Stevens’ incompetence in ship handling was demonstrated time and again in the course of his command of Voyager, the most telling example of which was his initiative, as the ship was undertaking the delicate process of towing the 28,000 ton aircraft carrier HMS Hermes in the sea to the south of Japan, of ordering an irresponsible sudden increase in speed.[23] The rupture of the steel tow line that resulted would almost certainly have resulted in the death of several of the crew had the officers attending, foreseeing what would transpire, not ordered the immediate clearing of the decks (Breaking Ranks, p. 146). If there had been no other mark against Stevens this incompetence ought to have been sufficient to ensure the Navy never placed him in charge of any of its ships.

It is entirely consistent that this incompetence at ship handling marked Stevens’ last order, given some 30 seconds prior to the collision with Melbourne, when he overrode the order of Lieutenant Commander Price, Officer of the Watch, to put the engines astern, and ordered full speed ahead and full right rudder. Price’s order was the correct one. (Whether it should have been coupled with full left or full right rudder depended on the attitude of each ship and their relative attitude to each other.) Price’s action, initiated so late, would not have prevented a collision but must have entailed less serious consequences and, in all likelihood, much less loss of life than transpired. ________________________________________

[1] See Tom Frame, The Cruel Legacy, the HMAS Voyager Tragedy, Sydney (Allen & Unwin), 2005, p. 27. [2] Tom Frame, Where Fate Calls, the HMAS Voyager Tragedy, Sydney (Hodder & Stoughton) 1992, p. 21, Note, this refers to visibility while the sun was in the sky. [3] Where Fate Calls, op. cit., p. 21. [4] According to Capt. Robertson. The Melbourne signals register puts the time at 2047 [5] According to Capt. Robertson. The Melbourne signals register puts the time at 2054, some two minutes later. [6] The second thoughts in the evidence of O/S Alex Degenhardt, the only survivor from Voyager's wheelhouse, that there had been an order 'midships' with a course to steer that might have been 032, should not be ignored. The Commissioner, Spicer, found in this evidence reason for holding that Voyager had settled on a course to the west prior to the collision, but he misunderstood the significance of what Degenhardt had said. A course of 032 could never have resulted in the collision: but that course might well have been given between the two orders, 'starboard 15' and 'port 10'. Robertson seems to confirm such a course when he said that after the initial turn to starboard Voyager had appeared to him to steady on about 065 before the turn to port commenced [7] Price gave an order some seconds prior that the engines should be put astern [Sumpter at Where Fate Calls p. 72] but this was immediately overridden. See the note in the appendix on the Captain’s ship handling. [8] Where Fate Calls, op. cit, pp. 73-4. [9] Where Fate Calls, op. cit., p. 74. [10] Where Fate Calls, op. cit. p. 76. [11] Where Fate Calls, op. cit., p. 76. [12] Cf. Where Fate Calls, op. cit., p. 78 for this and other confirming evidence. [13] Cf. The Cabban Statement, cited in Frame, op. cit., at p. 392. [14] Where Fate Calls, op. cit., p. 19. [15] Frame, citing Naval regulations in Where Fate Calls, op. cit., p. 19. [16] A 'point' in nautical terminology is 11¼º of a circle – 11 degrees 15 minutes of arc – one 32nd of the 360° circuit of the compass. Each navigation light, then, shines through an arc of 10 points from dead ahead and occludes at 22½° abaft the beam. [17] Evidence of Hyland to the first enquiry, quoted in Where Fate Calls, op. cit., at p. 79. [18] Where Fate Calls, op. cit., p. 390. The post mortem report on Stevens’ body revealed that his blood alcohol reading was 0.025 per cent (Tom Frame, The Cruel Legacy, Sydney, 2005, p. 151). Frame relates the accepted science that blood/alcohol content reduces by 0.02 per hour. Given that Stevens had imbibed the brandy provided him by his steward some 90 minutes before the collision it must be concluded that he had imbibed other alcohol as well. [19] The Cabban Statement; cf. Where Fate Calls, op. cit„ p. 386. Cabban qualifies this statement with the following— “In defence of Captain Stevens, he didn't consider that this should be taken seriously by the officers; after the event he expected them to learn and then to forget the tone in which he spoke. This took quite a bit of learning...” The qualification can be ignored in the circumstances of 10th February 1964 where there was an almost completely new crew. [20] Reported by Frame in Where Fate Calls, op. cit., p. 17. [21] Where Fate Calls, op. cit., p. 19. [22] Where Fate Calls, op. cit., p. 390. [23] In his tape recording that was reduced to writing and endorsed by him as ‘The Cabban Statement’, Cabban misnames the aircraft carrier involved in this incident as the Ark Royal. |